|

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society Home

: Document Collection Home

Use the links at the left to return.

|

Document Collection |

|

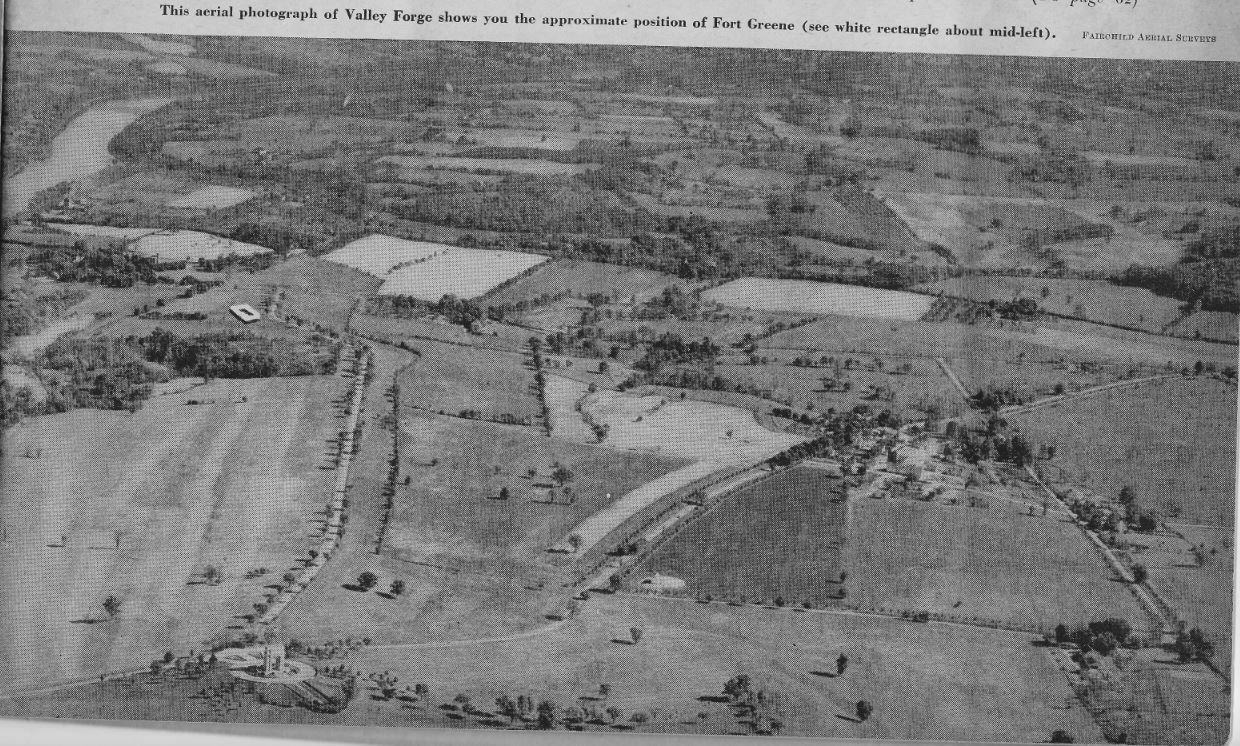

The mystery of the misplaced fort was too long unsettled. So they opened the case by starting an investigation of the ... “Disturbance” on the HillBy Roy A. GallantI am privileged to extend the best wishes of the Department of Defense to the Boy Scouts of America on the occasion of their second National Jamboree. It is fitting that this gathering of 40,000 Scouts and Explorers from all areas of the United States and Territories is being held at Valley Forge. For the grounds on which these boys and young men will pitch their tents are hallowed in our country’s history by the deeds of patriots who suffered and died to make this a free nation. The locale of the Jamboree cannot fail to deepen in them an appreciation of their national heritage and to broaden their spiritual ideals. Conscious of the valuable services of the Boy Scouts in the paper collection and in other conservation drives in support of the recent war effort, the Armed forces are gratified at the opportunity to greet the 2,500,000 Scouts and Explorers and their leaders and to wish them a successful celebration of the 40th Anniversary crusade of the Boy Scouts of America and continuing high adventure in their service to the American community. - Louis Johnson Secretary of Defense “THE POINT IS, THEY might have attacked. And Washington wasn’t in a position to take chances,” General Randolph said climbing to the top of the fire step and pointing off across the broad expanse of field toward the muddy Schuylkill River. The sun was warm. A gentle breeze carried the fresh scent of dogwood into the revolutionary war site where the General and I stood. In silence I looked down across the long green field and envisioned wave on wave of red-coated British troops steadily advancing up the slope into the booming cannon and cracking rifle fire of a handful of tattered men crouched behind the four dirt banks which formed Fort Greene. “Chances are they would not have made it,” General Randolph said suddenly, as though intercepting my thoughts. “From this spot Washington’s men had command of all that flank out there. And with the combined cannon fire from Fort Muhlenberg and Star Redoubt, the British would have had a rough time of it. There’s a lot of open field between here and the river.” The General’s voice was mild, but authoritative. It somehow reflected the reminiscence of a soldier who had once led his campaigns on the battlefield, but now looked back into the past to unveil forgotten accounts and lost battle sites of an earlier campaign - that of the American Revolution and the recently resurrected Fort Greene at Valley Forge. Digging up the original site of a fort that’s over 170 years old isn’t as easy as you might think. You don’t say to yourself, I guess it was about here, then start digging.You have to get airplanes with cameras, military strategists and a crew of energetic human gophers who are willing to dig until they turn up what you’re looking for. Tradition Was Wrong Before General Randolph asked Air Force photographers to take an aerial mosaic of the area which he thought hid the fort site, he read volumes of French and English texts on the form and construction of late eighteenth century military fortifications. Prior to the digging, the General first wanted to know precisely what he was looking for. This research coupled with his knowledge of battle techniques told him one thing for certain: the traditional site of Fort Greene formerly known as Fort John Moore, a land owner, was wrong. The old fort should have been higher up on the hill where its defenders would have a better command of the surrounding terrain. But it was time for the pictures to be taken and General Randolph was anxious to see what they’d reveal.

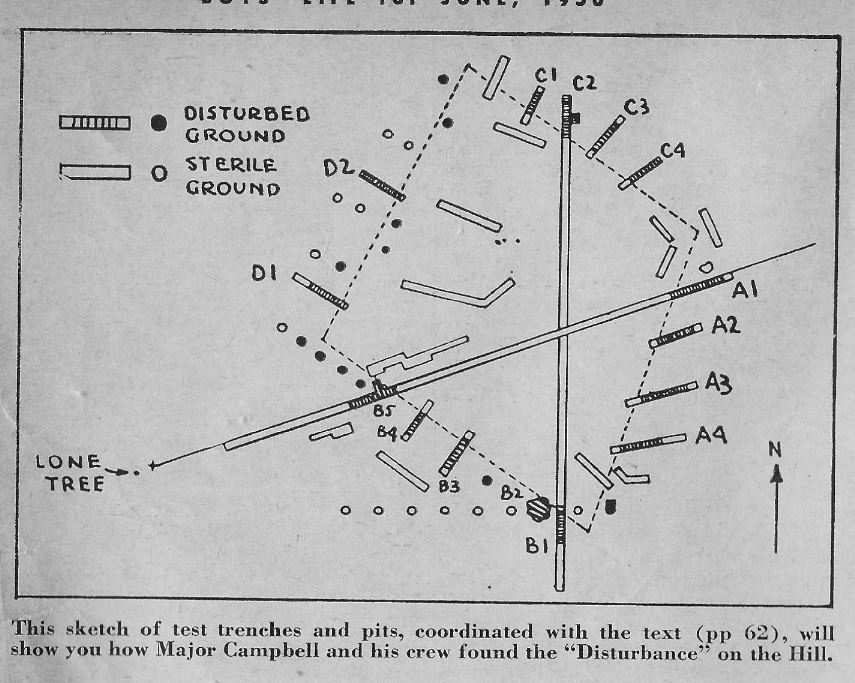

On one of the photos and about a quarter of a mile from the traditional site, the General detected four thin lines in the form of a trapezium (sort of lopsided square). From the ground the lines were invisible, but on the air photos their difference in coloration was distinct and represented soil disturbances which could well be the original site of Fort Greene (renamed after Nathaniel Greene, Washington’s left wing commander). One way to find out was to start digging. And this is where Major J. Duncan Campbell. a military archeologist, came in. He told General Randolph that within six weeks he’d be able to say definitely whether or not the fort’s original site was where the photographs showed it to be. To muster help the Major put a want ad in the Norristown paper. Within a few days three vacationing students - two of them bop artists, the third a photographer - answered Major Campbell’s summons and asked if they could help him dig. Allan Lightkep, Tommy Bray and Dick Kratz - all three of them had been scouts - were eager for a sun and muscle campaign. And this was it. Before they began the pick and shovel work, the Major warned them: “Now we may dig up bones, old military buttons, musket balls and I don’t know what else, so be careful. And if you do turn anything up, yell it out.” They Begin the Digging That was all the boys needed - the excitement of digging for treasure - well an archeologist’s treasure anyway, and that’s what Allan, Tommy and Dick had become, young archeologists. Stripped down to the waist under a hot August sun, the boys began digging a trench three feet wide, uprooting the chocolate top soil which was about eleven inches deep; They were digging along a line running northeast from a lone tree to a stone troop marker (see Test Trench and Pit Sketch). “According to the aerial photograph this line should have cut through two sides of the fort,” Major Campbell explained. “And we expected to find our first disturbance [an irregularity in the soil] about ninety-three feet from the tree. But nothing happened.” At ninety-seven and a half feet however, the young excavators hit their first disturbance, B-5. here, the chocolate top soil was deeper than it should have been. This told the boys they had hit an ancient ditch or hole which over the years had been gradually filled in by eroded top soil. So you see now why at B-5 the chocolate soil went deeper than that of the rest of the trench. The plan, after finding this first disturbance, was to continue digging in the same line from the lone tree and hope that the Major’s crew would hit a second side of the fort as the mosaic photographs indicated they would. “He Flies Through the Air ...” To make the digging easier the Major and his human gophers borrowed a tractor and scoop. Here’s the way it worked: one man in the tractor towed the scoop which was guided along by the other man. pushing the scoop handles up and down determined the bite-depth the shovel-like front end would take. Well, the Major tried it first but found himself flying through the air and crashing down in a heap just behind the tractor. “You took too big a bite,“ Allan shouted laughing. “Keep the scoop handles lower next time.” After the Major brushed off his indignation he had Allan try it. Everything went fine for the first twenty feet, then suddenly Allan took a dive over the top and came down in a floudering belly flopper. A few yards beyond, the chocolate top soil suddenly became deeper. This second disturbed zone they marked A.1 and felt strongly they had hit the second side. Disturbed ground at B-1 was next found, and from this point an imaginary line was projected to the inside edge of B-5. While Dick and Tommy dug additional test trenches and found more disturbances at B-3 and B-4, the Major and Allan struck it rich, in A-2, A-3 and A-4. The completion of A-4 now made it possible to establish two sides and the south corner of the fort site. “Our job was difficult,” the Major said. “We had no decayed wood or stone walls to give us material evidence of a former construction. Many times we found ourselves walking on eggs. In our hearts we wanted to believe the old fort was there, but we had to rely completely on our own digging and the disturbances we came across.” Several times when Major Campbell and his crew stumbled onto a problem which seemed insoluble, they felt like giving up. However, every time they reached a low point they heard the familiar sound of a jeep churning its way up the hill. It was General Randolph. His interest and enthusiasm for the project never failed to put the gang back to work again with high hopes. Two other indispensable problem-solvers were Dr. J. Alden Mason, of the University Museum, Philadelphia, and John Witthoft of the Pennsylvania Historical Museum, Harrisburg. “There’s Bone Down Here” To find the third side of the fort, Allan wrestled with the scoop again and headed due north. By now he had it tamed. A new disturbance at C-2 was found. Tommy began digging this northeast wall ditch. Suddenly, his shovel struck something hard. “Hey,” he yelled, “there’s bone down here. Come look.” It was a calf’s skull buried about four feet deep. “How come just the skull?” Tommy asked the Major. “What about the rest of the animal?” Major Campbell explained that during the winter of 1777 and 1778 Washington’s troops were nearing starvation, so they ate nearly anything on four legs, including colts. The skull which was in excellent condition because of its limestone bed, was most likely the sole remains of a young cow eaten by the Continental soldiers that made up the Fort Greene troops. The boys next dug test trenches C-1, C-3 and C-4 and found disturbances in each one. Along the bottom of this northeast ditch the Majors crew found hundreds of chunks of field stone evidently dumped by some colonial farmer when he cleared his land for plowing. Next, by projecting the northeast and southeast sides of the fort, it was possible to establish the east corner. The next problem was to locate the northwest side. Try a Shotgun Pattern “That fourth side really had us confused,” Major Campbell said. “B-5 seemed to be a corner. And since the test trench to the left of C-1 was sterile [no disturbance found] we assumed that both B-5 and C-1 were corner. But we found out we were wrong when we dug four more sterile test trenches in a line between B-5 and C-1.” There was another possibility: to dig test pits about the size of barrelheads in a line northwest from B-5. Disturbances were found in four of them. The fifth however, was sterile, so the Major knew his crew had gone beyond the remaining fourth side. A shotgun pattern of test pits was next dug along the fourth side. Of these pits, four showed disturbances. Five did not. D-1 and D-2 were next dug to determine the width of the northwest trench. Up to his knees in D-2, Allan suddenly shouted, “Hey, Major, I think I’ve hit a bayonet.” It turned out to be a hand-forged eighteenth century sickle. An Entrance to the Fort The two side-by-side test pits just north of D-2 offered the crew of fort-diggers their last problem. Because these pits were sterile, it appeared that the northwest trench had a break in it. And it did. A historian named Woodman who had written about Fort Greene over a hundred years ago, described “a point of egress” on the northwest side. This point turned out to be the non-trenched ground north of D-2 and was used a path for moving light artillery. With this last problem solved the General, the Major, Allan, Dick and Tommy packed up their tools. They had spent 650 hours digging, and in exactly thirty days had resurrected from a dormancy of nearly two centuries, the meager remains of a revolutionary encampment. In addition, they had put an official seal of confirmation on historian Woodman’s statements by proving false the legendary position of Fort Greene. A General at Twenty-six Fort Greene’s present location fits neatly into the strong network of the four other redoubts. These defensive positions to the terrain for maximum observation and field of fire - were thought out and engineered by twenty-six-year-old General Duportail. And it was because of his work that Sir William Howe, Commander of the British forces reported “... having good information in the spring that the enemy [our Continental forces] had strengthened his camp by additional works, I dropped all thoughts of attack.” Shortly after the American Revolution, Duportail was called back to France by Napoleon. But his brilliant career was suddenly brought to a close by his death en route. Why didn’t the British attack? Well, one of the reasons is this: the strategic position of Fort Greene (and other artillery redoubts) would have placed the British at a decided disadvantage, according to most military observers. But when you inspect Fort Greene, looking down across the field on the Schuylkill, imagine yourself one of the young men who crouched behind those dusty mounds of dirt, waiting for the attack they expected. Some of them weren’t much older than you are. References and Notes1. June 1950 issue of Boy’s Life. Found by Jim Brazel. 2. Dr. J. Alden Mason was a founder member of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club (as it was then known). 3. The following satellite photograph from Google shows Redoubt #2 close to the excavations of Fort Greene. There is a second redoubt south of Outer Line Drive which may be located at the traditional location of Fort Greene. |